What's the opposite of discomfort?

What an awkward birthday present taught me about creative practice

The day I turned 30, my boyfriend Jacob gave me a terrible gift.

“I hope you like it,” he said with a clumsy smile, and handed me a small brown paper bag.

I reached into the thin, crinkly bag and pulled out a navy, pocket-sized Moleskine. It was hardcover, expensive-looking. A tiny…journal? I tore off the clear plastic wrap and flipped it open, but instead of blank or college-ruled pages, each page held a series of five parallel, faint blue lines: Bass and treble clef. For writing sheet music.

I couldn’t read sheet music.

“What a thoughtful gift!” I lied, and pecked him on the cheek. What I meant to say was: “Maybe we shouldn’t be dating.”

Jacob had unknowingly bumbled right onto one of my emotional landmines: Despite having played music professionally for ten years, I’d never learned music theory. I’d recorded four records, played nearly a thousand live shows, but I couldn’t tell a B♭ from a C♯ to save my life. I chalked my lack of knowledge to an inherent lack of discipline. It was an insecurity that plagued me since the day I picked up the guitar.

I was 17 when it first occurred to me that I might play music. I was camped out on a beige corduroy couch at Espumas, a coffee shop in downtown Laredo, when a guy with long black curls and cumin-colored skin sat at the head of the room with an acoustic guitar. He strummed the chords to Radiohead’s “Fake Plastic Trees,” singing the opening line in a gentle, nasally falsetto, and the vintage lamps and chandelier buzzed and brightened. The chatter in the cafe fell to a hush. TI was wrapt. At that age, I was lonely and awkward and fashioned myself to be aggressively indie for South Texas, listening to Tori Amos and Ani Difranco and reading books like Prozac Nation. It felt like a miracle of taste to encounter another human three hours south of Austin who had similarly eclectic taste. “I wrote this next song,” he said, and my admiration morphed into envy. I didn’t want him so much as I wanted to command his attention. His, and everyone else’s.

A week later, I scraped up enough cash from my $5.15/hr cafe barista job and waltzed into Guitar Center. I picked out an $85 sunburst-blue Rogue Starter Acoustic, my first guitar. While there, I grabbed the sheet music songbook to Fiona Apple’s When the Pawn—what, like it’s hard? I drove home with the V-shaped cardboard box perched in the backseat of my brother’s hand-me-down silver Jetta, “OK Computer” blasting on the stereo, feeling triumphant. I’d always been a good performer, so it stood to reason that I would be a good musician, too. Within a week or two, I was sure, it would be me folded over my blue cutaway at Espumas, crooning a Sarah McLachlan cover while that curly-haired guitarist looked on, adoringly.

But when I got home and tore it from the cardboard box, what emitted from the guitar was not music. It was jangly noisecrap. I stretched my fingers, and strummed it once, twice. More noise. What’s worse, it hurt. I felt stupid. After five minutes, I laid the guitar on the carpet and walked downstairs to the kitchen for some cookies, wondering if I’d managed to bring home the one broken guitar in the shop.

I had no clue a guitar needed to be tuned.

I convinced my parents to pre-pay for a month’s worth of guitar lessons at the local music school. At my first 30-minute lesson, the 20-something-year-old guitar instructor walked me through proper fingerpicking form (which, ow) then handed me the Hal Leonard Guitar Method Book and told me to go home and practice “Greensleeves.” He might as well have asked me to sing the alphabet in braille. I struggled to understand how the notes on the page in front of me corresponded with the frets on the guitar. Playing was painful. I didn’t practice, and when I showed up for my group lesson later that week, I was schooled by two 7-year-old boys in the group, who plucked through the British folksong with ease. I felt humiliated. After that, I never went back.

I dragged that guitar around the world for three years, eventually teaching myself to read the numerical scale for guitar tabs online. It took me twice as long as it takes most guitarists, but I built up just enough finger strength to write simple, sparse tunes. I learned the basic techniques, but never theory.

I continued to sidestep anything that threatened my ego—fingerpicking instead of learning strum patterns, strumming in “free time” too avoid rehearsing to a metronome, writing songs in quirky, alternative scales to avoid practicing painful bar chords. People told me I had a unique style—in reality, I took creative shortcuts to avoid feeling incompetent. At late-night jams around Austin, musicians would ask me what key a song was in, or worse, shout out the corresponding Roman numerals to the chord progressions of one of their songs, and I would stare back wide-eyed, dumb as a fish, reaching for an egg shaker so as not to be found out an amateur.

So when Jacob handed me that music notebook, he had no clue it was a loaded hot potato of harsh, shitty feelings. I accepted his gift, pantomiming something like gratitude, and tossed it into the bottom of my “everything” desk drawer. I just wasn’t that kind of guitarist. It would always be that way. Undisciplined, unstudious, unskilled.

I now know it was all ego—I’d slipped right into what social scientist Carol Dweck calls a “fixed mindset.” I believed my abilities and talents were inherently fixed, frozen in time. Some things I was good at—performing, acting, bullshitting my way through English papers. But anything that required frequent failure, like math, science, and theory, just wasn’t my thing.

The next year, burnt out from 10 years of touring and freelancing, I went back to college. I signed up for an Intro to Creative Writing course at Hunter College and loved it. Maybe I wasn’t a shitty student after all? On a gut whim, I dared myself to register for one more course—Introduction to Music Theory.

On day one, our professor, a wiry adjunct with salt-and-pepper hair, announced that he would begin each class by calling a series of students to the board to identify notes on the music staff. I blanched.

“Practice,” he told us. “All of this is practice. You’ll probably feel stupid—at first.”

I went home and fished the navy Moleskine notebook out of my everything drawer, then I got to work. Over the next 6 weeks, I darkened page after page with handwritten half, whole, and quarter notes. He was right: Many times I got called up to the board, wanting to vomit, and got it wrong. We all did. The world kept turning.

I realized then that the key to moving through discomfort was almost always to check my own ego. If I resisted practicing, studying, and writing, it was usually because I was worried about looking or feeling dumb, or worse—projecting some invisible other, judging me.

I aced that class and I got into the New School, where I signed up for Introduction to Piano. I bought the same Fiona Apple Songbook I’d walked out of Guitar Center with when I was 17, learning “Paper Bag” at a near-glacial pace. Evenings after class, I rode the 6 train, drumming the syncopated notes on my thigh like morse code. It was slow going, but every day, it got easier.

The irony is that, after those two courses, I never used theory again. I didn’t need to—by then I’d mostly stopped playing shows. The point wasn’t to learn music theory—it was to change my beliefs. I needed to cast enough votes for myself to prove that I wasn’t defective, lazy, or incapable. I just had a fragile ego. And I really, really craved others’ approval. Once I knew this about myself, I knew what to do—just push through those initial moments of struggle. I would feel stupid again. But I wouldn’t feel that way forever.

Last week I turned 37. After weeks of banging my head against my book-shaped wall, I took the day off to hike in the Poconos with my friend, Jeanie. Afterward, cuddled up on her couch, Jeanie handed me a small rectangular box.

“It might be wildly off base, I don’t know,” she said, with a shy smile.

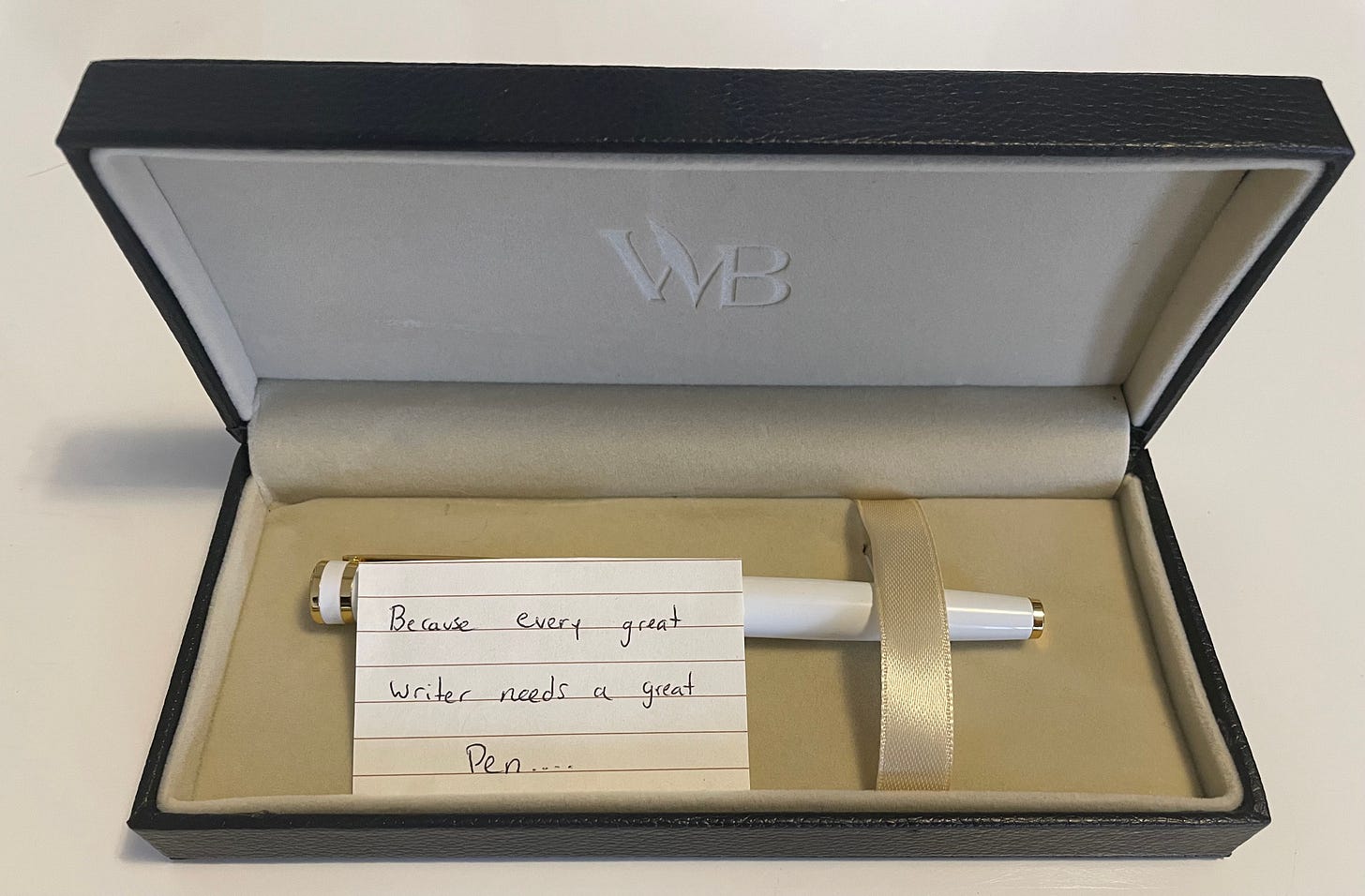

I popped open the box, and picked up a little note that she’d written: “Because every great writer needs a great pen….”

I placed the note aside, and underneath it was a white and gold fountain pen.

I thought back to the Moleskine that Jacob had given me, the humiliation I’d felt, and for a moment, I was haunted by the same old fear.

“You know, I read this and the first thing that came to me was: But I’m not actually a writer,” I told Jeanie. We laughed.

I installed the ink cartridge, grabbed my Composition notebook, and then I did the same thing I’ve done nearly every day since January: I wrote three long-form, shitty-first-drafty pages.

I am writing this now as a reminder, as I wade further into writing life. But also, I hope, to you. To all of our former selves, the ones we still lug around alongside us with beliefs about our fuck ups and failures, the parts assured they will never, ever make it to the other side of some uncomfortable skill or habit or dream.

My writing still isn’t where I want it to be—and that’s okay. Just as I eventually learned to read tabs, chords, and entire pages of notated music, I’ll continue studying craft, reading widely, and seeking out guidance. It’s practice. A practice, I’ve learned, is not like riding a bike. More like riding a horse. You have to move through the awkward, bumpy beginning trot before you reach a smooth, steady gallop. It’s fucking uncomfortable—at first. Stick with it long enough, and eventually you’ll ease into a stride. Eventually, you look up and get lost in the breadth of the desert landscape, and you remember all the reasons you fell in love with riding in the first place.

For me, the opposite of discomfort isn’t ease. It’s humility.

So today, I am thinking sweetly back to that reactive 30-year-old who was all like “Fuck off, Jacob,” and reminding her to take a beat. Put in the pages. And maybe don’t be such a brat about birthday presents.

Where could you stand to be just a little bit uncomfortable?

With care,

Aly

PS. Speaking of writing, I’ve missed a few posts this month as I get a handle on Substacking vs bookwriting vs. teaching vs. freelancing. Thanks for sticking with me. I’m still here, albeit at a slower clip during semester crunch times.

Another piece that should be required reading for all college students! We’re so afraid of failure and looking “stupid” that we often forego taking on challenges that tap into our inner dormant strengths. It’s so liberating to branch out and leave the ego on the shelf. Look at all you’ve mastered. You should continue to give yourself daily “attagirl” claps on the back! 🙌🏻💖

This piece makes me want to clear off my desk and practice, and maybe play -- thank you, Aly. Absolutely love this reflection. ❤️